Primitivo

Near the Adriatic, close to where the Alimini Grande and Alimini Piccolo lakes meet, the growers at Menhir Salento tend their vines. “Our ancestors rarely planted vineyards in this part of the region as the soil was difficult to work with,” says enologist Marco Mascellani. “When we started in this area, we thought about what we wanted to achieve: elegant wines in a region of muscular wines. We knew it would cost more but it was results that mattered.”

Menhir Salento’s indigenous grapes have adapted to the area’s high average temperatures and poor rainfalls, creating a flavor like no other. “Primitivo, together with Negroamaro, are the most important varieties of Salento because they’re versatile. In fact, we can produce rosé wines, young reds, structured reds for aging, as well as sparkling wines from the same grape.”

As the second-largest wine region in Italy, Puglia has often played second fiddle to Tuscany with its exports. The tide, however, seems to be turning, with acclaimed producers like Vetrère, who produce award-winning bottles with nothing but clean energy, and Valentina Passalacqua, whose natural biodynamic wines grace the lists of world-renowned restaurants.

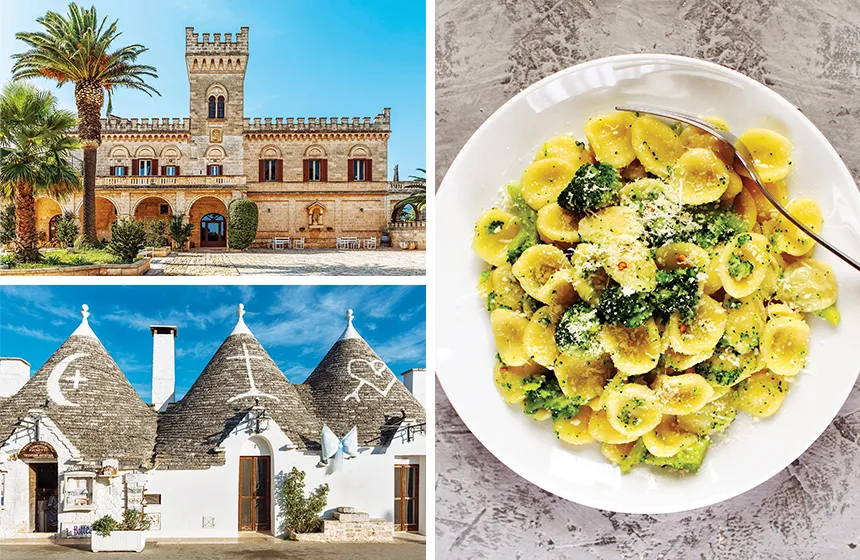

“Puglia is steeped in tradition,” says Mascellani, “but we believe that fusion and variety are the spice of life.” Enophiles will want to sample the bottles at the producer’s winery in the nearby small town of Minervino di Lecce. Located in a baronial palace dating back to the 18th century, their stone headquarters are also home to Origano Osteria, a farm-to-table restaurant that serves traditional Pugliese food (like braised veal cheek or seared octopus). The primary focus, however, remains the wines, with light refreshing whites like Pass-O Fiano or powerful reds like Numero Zero Negroamaro accompanying the dishes.

Pasticciotto

During the 12th Century, it was a sacred tradition for the Knights Templar to travel to the commune of Santa Maria di Leuca to pray before heading off to the Crusades. This is the spot where St. Peter first touched down in Italy, in the southernmost part of Puglia, commemorated centuries later by the construction of the Basilica Sanctuary of Santa Maria de Finibus Terrae, a sacred space that visitors need to book weeks in advance to tour.

Today, people journey south for a different kind of religious experience. They’re looking for pasticciotto, a shortcrust pastry filled with lemon custard. According to legend, the dessert was created in 1745 when pastry chef Nicola Ascalone was looking for something to feed pilgrims traveling to the region for the feast of St. Paul. Finding an excess of pastry and custard in his kitchen, he combined the two, baking them in a small copper mold.

The Martinucci Laboratory is where you will find some of the best takes on the classic. Founded in 1950 by Giovanni Martinucci and his son Rocco, the bakery has more than a dozen locations in Salento, each one offering visitors a taste of the original or a modern version made with black cherry, gianduja chocolate or pistachio.

“The best way to enjoy pasticciotto is when it’s still warm,” says Frulloni, who prefers to have his for breakfast along with a cappuccino. “Two hours out of the oven.” Although this sentiment is quite hard to fathom in most major cities in North America—where food is often pre-made and shelved for days—it is par for the course in Puglia. If any region illustrates the importance of eating Italian-style—aka treating the taste buds with reverence—it is here.